This post is about our next dust bowl, brought to you by way of satellites orbiting 440 miles above the earth.

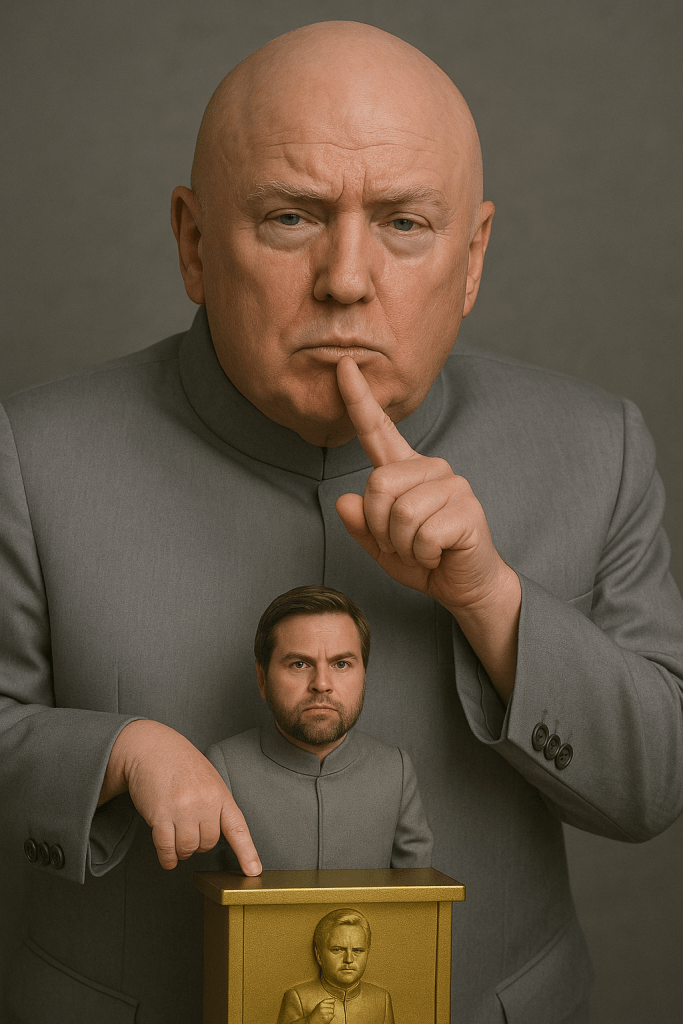

Last week, Trumpandlandia announced that it’s killing off the only two federally funded satellites doing climate research. The data they collect is critical. It’s used by scientists studying how to forestall the collapse of a livable planet and farmers trying to feed us so we don’t starve before we’re buried in lava. The satellites are called Orbiting Carbon Observatories, a far too plain and practical name that gives them away as scientific and therefore SAD! (They might’ve lasted longer behind a name like “Big Beautiful Birdies.”)

Since climate change is a global phenomenon, Earth-circling satellites are needed to understanding what we’re facing. And because for now we still have the best technology and scientists on Earth, these satellites also measure photosynthesis and therefore plant growth, not only crops, but rangeland and forests, as well as drought. Drought predicts crop failure which predicts mass migration which predicts socio-political stability, which … ah, forget it: Kill the Satellites. NASA calls the protocol for terminating perfectly good satellites paid for by taxpayers “Plan F.” You can guess what the “F” stands for. (It cost as much as $1B to put the satellites in space – but only $15M a year to maintain them.) Here’s a kicker, at the same time it’s preparing to destroy satellites at their peak of efficiency, NASA is open for business from private satellite companies. Musk to the rescue, again on the coattails of public funding.

FUN FACT: Each year, we put 36 billion tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, but only half of it stays there. Where does the rest go? These satellites were helping us figure it out.

Like everything else out of Trumplandia, when you peel back the layers, it gets weirder and weirder. The planet is up for grabs. Oil and gas drilling from the Artic Ocean to the Carolina Coasts, and millions of acres of public lands in between for sale. If it doesn’t feel like it yet, it will: this is your backyard. Not to worry, though, the EPA has ERASED the crucial, if decades late, 2009 “Endangerment Finding,” which admitted that human-made heat-trapping gases like carbon dioxide are a threat to humanity (and everything that lives). In other words, not our fault, so we’ll keep on extracting. Drying up fastest? That’s a tie between approval of solar and wind projects and enforcement against polluting coal, oil and gas companies.

The American Dustbowl of the 1930s was one of the worst environmental disasters in our history. It enveloped much of the Heartland. It lasted a decade. Bad farming policy is to blame. We over-did it; more and more cropland, less and less prairie. Then drought. The cost is impossible to calculate. Millions of acres turned to dust. Farms, livelihoods, lives lost. Despair.

But, as we always do, we put that behind us, thanks in large part to technology, and restocked America’s Breadbasket. About one-third of our grains, produce and meat come from there. Since the plains are semi-arid, almost all of this production depends on irrigation. There’s basically one source. It’s called the Ogallala Aquifer, and it stretches from South Dakota to Texas. We’re killing it, too. We are both depleting and polluting the Ogallala. In places, it’s already gone. This groundwater is millions of years old and irreplaceable. The end of the Ogallala is the end of the American Heartland.

The More We Take is a sometimes harsh, sometimes fantastical, yet hopeful story about how, first, we stole the prairie from the Plains tribes, murdering and jailing and separating Indigenous families, and second, we abused the stolen land because that meant more money.

All stories are true. The More We Take gives us a fighting chance at avoiding disaster. The chance is us. The fighters here are ordinary Nebraskans (a surveyor, a nurse, a manager) who get extraordinary help (Sitting Bull, Red Cloud, Crazy Horse) to take a stand for a better tomorrow. This is a scrappy, irreverent group of underdogs willing to organize and protest and take on Big Ag, and their little orbit attracts a colorful group — a rodeo star, a hippie farmer, a 10-year-old clairvoyant — who aren’t afraid to get caught trying.